Metronome Magazine: Miles Davis

Miles Dewey Davis III (May 26, 1926 – September 28, 1991) was an American jazz musician, trumpeter, bandleader, and composer.

Widely considered one of the most influential musicians of the 20th century, Miles Davis was, together with his musical groups, at the forefront of several major developments in Jazz music, including Bebop, Cool Jazz, Hard Bop, Modal Jazz, and Jazz Fusion.

In 2006, Davis was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, which recognized him as “one of the key figures in the history of jazz”. In 2008, his 1959 album Kind of Blue received its fourth platinum certification from the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA), for shipments of at least four million copies in the United States. On December 15, 2009, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a symbolic resolution recognizing and commemorating the album Kind of Blue on its 50th anniversary, “honoring the masterpiece and reaffirming jazz as a national treasure”.

In the fall of 1944, following graduation from high school, Davis moved to New York City to study at the Juilliard School of Music. Upon arriving in New York, he spent most of his first weeks in town trying to get in contact with Charlie Parker, despite being advised against doing so by several people he met during his quest, including saxophonist Coleman Hawkins.

Finally locating his idol, Davis became one of the cadre of musicians who held nightly jam sessions at two of Harlem’s nightclubs, Minton’s Playhouse and Monroe’s. The group included many of the future leaders of the bebop revolution: young players such as Fats Navarro, Freddie Webster, and J. J. Johnson. Established musicians including Thelonious Monk and Kenny Clarke were also regular participants.

Davis dropped out of Juilliard after asking permission from his father. Davis began playing professionally, performing in several 52nd Street clubs with Coleman Hawkins and Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis. In 1945, he entered a recording studio for the first time, as a member of Herbie Fields’s group. This was the first of many recordings Davis contributed to in this period, mostly as a sideman. He finally got the chance to record as a leader in 1946, with an occasional group called the Miles Davis Sextet plus Earl Coleman and Ann Hathaway—one of the rare occasions when Davis, by then a member of the groundbreaking Charlie Parker Quintet, can be heard accompanying singers.

Around 1945, Dizzy Gillespie parted ways with Parker, and Davis was hired as Gillespie’s replacement in his quintet, which also featured Max Roach on drums, Al Haig (replaced later by Sir Charles Thompson and Duke Jordan) on piano, and Curley Russell (later replaced by Tommy Potter and Leonard Gaskin) on bass.

With Parker’s quintet, Davis went into the studio several times, already showing hints of the style he would become known for. On an oft-quoted take of Parker’s signature song, “Now’s the Time”, Davis takes a melodic solo, whose unbop-like quality anticipates the “cool jazz” period that followed. The Parker quintet also toured widely. During a stop in Los Angeles, Parker had a nervous breakdown that landed him in the Camarillo State Mental Hospital for several months, and Davis found himself stranded. He roomed and collaborated for some time with bassist Charles Mingus, before getting a job on Billy Eckstine’s California tour, which eventually brought him back to New York. In 1948, Parker returned to New York, and Davis rejoined his group.

By December of 1948, Davis left the group which marked the beginning of a period when he worked mainly as a freelancer and sideman in some of the most important combos on the New York jazz scene.

Birth of the Cool

(1948–49)

In 1948 Davis grew close to the Canadian composer and arranger Gil Evans. Evans’ basement apartment had become the meeting place for several young musicians and composers such as Davis, Roach, pianist John Lewis, and baritone sax player Gerry Mulligan who were unhappy with the increasingly virtuoso instrumental techniques that dominated the bebop scene. Evans had been the arranger for the Claude Thornhill orchestra, and it was the sound of this group, as well as Duke Ellington’s example, that suggested the creation of an unusual line-up: a nonet including a French horn and a tuba (this accounts for the “tuba band” moniker that became associated with the combo).

Davis took an active role in the project, so much so that it soon became “his project”. The objective was to achieve a sound similar to the human voice, through carefully arranged compositions and by emphasizing a relaxed, melodic approach to the improvisations.

The presence of white musicians in the group angered some black jazz players, many of whom were unemployed at the time, but Davis rebuffed their criticisms.

A contract with Capitol Records granted the nonet several recording sessions between January 1949 and April 1950. The material they recorded was released in 1956 on an album whose title, Birth of the Cool, gave its name to the “cool jazz” movement that developed at the same time and partly shared the musical direction begun by Davis’ group.

Hard bop and the “Blue Period”

(1950–54)

Despite all the personal turmoil, the 1950–54 period proved to be a fruitful for Davis artistically. He made quite a number of recordings and had several collaborations with other important musicians. He got to know the music of Chicago pianist Ahmad Jamal, whose elegant approach and use of space influenced him deeply. He also definitively severed his stylistic ties with bebop.

In 1951, Davis met Bob Weinstock, the owner of Prestige Records, and signed a contract with the label. Between 1951 and 1954, he released many records on Prestige, with several different combos. These recordings, their quality is almost always quite high, document the evolution of Davis’ style and sound. With these recordings, Davis assumed a central position in what is known as hard bop. In contrast with bebop, hard bop used slower tempos and a less radical approach to harmony and melody, often adopting popular tunes and standards from the American songbook as starting points for improvisation. Hard bop also distanced itself from cool jazz by virtue of a harder beat and by its constant reference to the blues, both in its traditional form and in the form made popular by rhythm and blues.

KIND OF BLUE (1959–64)

In March and April 1959, Davis re-entered the studio with his working sextet to record what is widely considered his magnum opus, Kind of Blue. The resulting album has proven both highly popular and enormously influential. According to the RIAA, Kind of Blue is the best-selling jazz album of all time, having been certified as quadruple platinum (4 million copies sold).

Electric Miles (1968–75)

Davis’s influences included 1960s rock and funk artists such as Sly and the Family Stone and Parliament/Funkadelic, many of whom he met through Betty Mabry (later Betty Davis), a young model and songwriter Davis married in September 1968 and divorced a year later. The musical transition required that Davis and his band adapt to electric instruments in both live performances and the studio. By the time In a Silent Way had been recorded in February 1969, Davis had augmented his quintet with additional players. At various times HerbieHancock or Joe Zawinul was brought in to join Chic Corea on electric keyboards, and guitarist John McLaughlin made the first of his many appearances with Davis.

Davis recorded the double LP Bitches Brew, which became a huge seller, reaching gold status by 1976. This album and In a Silent Way were among the first fusions of jazz and rock that were commercially successful, and helped to fuel a genre that would become known as jazz fusion.

Both Bitches Brew and In a Silent Way feature “extended” (more than 20 minutes each) compositions that were never actually “played straight through” by the musicians in the studio. Instead, Davis and producer Teo Macero selected musical motifs of various lengths from recorded extended improvisations and edited them together into a musical whole that exists only in the recorded version. Bitches Brew made use of such electronic effects as multi-tracking, tape loops, and other editing techniques. Both records, especially Bitches Brew, were big sellers. Starting with Bitches Brew, Davis’s albums began to often feature cover art much more in line with psychedelic art or black power movements than that of his earlier albums. He took significant cuts in his usual performing fees in order to open for rock groups like the Steve Miller Band, Grateful Dead, Neil Young, and Santana. Davis recorded several live albums including: Live at the Fillmore East, March 7, 1970: It’s About That Time (March 1970), Black Beauty (April 1970), and Miles Davis at Fillmore: Live at the Fillmore East (June 1970).

WOrk with the

New-Wave PuNk Movement

Davis collaborated with a number of figures from the British post-punk and new wave movements, including Scritti Politti. At the invitation of producer Bill Laswell, Davis recorded some trumpet parts during sessions for Public Image Ltd.’s Album, according to Public Image’s John Lydon in the liner notes of their Plastic Box box set. In Lydon’s words, however, “strangely enough, we didn’t use [his contributions].” According to Lydon in the Plastic Box notes, Davis favorably compared Lydon’s singing voice to his trumpet sound during these sessions.

Davis died on September 28, 1991, from the combined effects of a stroke, pneumonia and respiratory failure in Santa Monica, California, at the age of 65. He is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx.

Views on his earlier work

Late in his life, from the “electric period” onwards, Davis repeatedly explained his reasons for not wishing to perform his earlier works, such as Birth of the Cool or Kind of Blue. In his view, remaining stylistically static was the wrong option. He commented: ” “So What” or Kind of Blue, they were done in that era, the right hour, the right day, and it happened. It’s over […] What I used to play with Bill Evans, all those different modes, and substitute chords, we had the energy then and we liked it. But I have no feel for it anymore, it’s more like warmed-over turkey.” When Shirley Horn insisted in 1990 that Miles reconsider playing the ballads and modal tunes of his Kind of Blue period, he demurred. “Nah, it hurts my lip,” was the reason he gave.

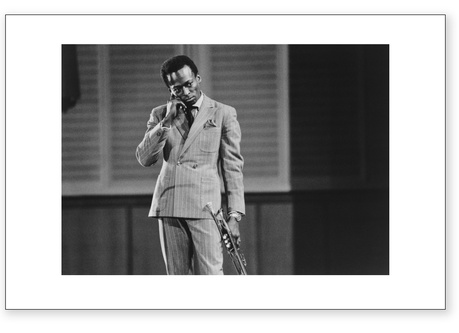

Miles Davis in a pensive moment as he performs on stage in West Germany.

Miles Davis “On Stage in West Germany”

Photographer: Michael Montfort

Year Photo Taken: 1959

See all Miles Davis posters and items for sale on Limited Runs

Back to Artist List

Back to Metronome Main Page